As I entered the bosque of adolescence, I was lucky. I had my particular bible. It was a thin book with brown and brittle pages that had not held up well to use and age. On the cover was Perseus, winged sandals on his feet, a thick sword in his right hand and in his left the head of Medusa, her scalp dripping with snakes. The book was called, simply, Mythology, by Edith Hamilton, and in its pages I found the gods, heroes and monsters who accompanied me through one of the darkest periods of my life.

As I entered the bosque of adolescence, I was lucky. I had my particular bible. It was a thin book with brown and brittle pages that had not held up well to use and age. On the cover was Perseus, winged sandals on his feet, a thick sword in his right hand and in his left the head of Medusa, her scalp dripping with snakes. The book was called, simply, Mythology, by Edith Hamilton, and in its pages I found the gods, heroes and monsters who accompanied me through one of the darkest periods of my life.

At first they seemed dubious chaperones, especially the gods. Zeus was the worst of them, harassing and deceiving the ladies at every opportunity. He’d turn himself into a swan, a bull and, in one account, a disheveled cuckoo. He’d appear as a shower of gold. He’d sweettalk, connive, rape and impregnate young women and pay no child support. The goddesses had their own deficiencies; they tended toward melancholy and jealousy, infighting and favoritism. And though the mortal heroes and heroines were more demure, more rational, all that disappeared when the gods got hold of them to carry out some mission to serve their godly purposes. The monsters were intriguing but hardly comforting. They were hundred-eyed, many-headed and tentacled. There were Gorgon women with tusks, wings and claws and a gaze that could turn mortals to stone. There were centaurs, a Minotaur and Cerberus, the three-headed guard dog of Hell. These were my mentors.

To paraphrase Saint Paul, the invisible is best understood by the visible. The Greek and Roman myths are the unconscious made conscious, the unseen come to light. They are metaphor on a grand scale, and they were my introduction to the healing power of story, imagination, and the blending of real and unreal. I understood their job was not to comfort me but to strip away the protective layer of falsehoods and misunderstandings that had thickened around me like plaque. I knew the world to be a safe place, a welcoming place, but it was not. There were monsters to slay, parents and children at war with one another, fathers killed by sons and sons killed by fathers. We were the monsters. There was no safe place for women, no one could be trusted, and jealousy abounded and sometimes led to death. Love triumphed and failed, and those who loved risked punishment from the gods. The gods were created in our image and they too were the monsters. It was a time of necessary awakening for me, and my bible Mythology sharpened the process. I spent a full year walking around in my life with that thin book in my pocket. I read it on the bus on the way to school. I read it in my room with my door shut against my family. I read and reread it to absorb the news it brought me—that around me swirled a world of pain. And I read it to understand the nature of that pain which encompassed my own adolescence. I kept reminding myself: We are the monsters.

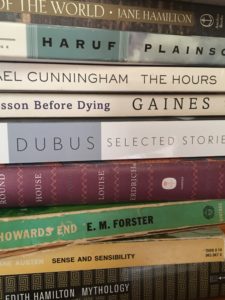

That time ran its course, and I came to believe in other things. We were monsters, yes, and gods, and most of all and most interestingly mortals. Other books came for me. I was a slow and careful reader; without knowing it I was studying the craft. How was that illusion created? Why so many adverbs? Ah, the shorter sentences create a sense of urgency, like boots pounding the ground. I was learning the art of artifice. I was Pygmalion with a pencil. I had turned a corner, leaving Edith Hamilton and her pantheon behind. I was interested in humans. I was interested in maps. I was smitten by the night sky and thoughts of an edgeless universe. I read in foreign languages and in Jane Austen’s English which seemed foreign. And when my brother was mugged and given a one-in-ten chance to live, I spent two weeks beside his hospital bed listening to the shudder of the machines to which he was attached, reading E.M. Forster’s Howards End. I have the copy still, complete with notes like: D. back from the dead, sat up and asked for a piece of scorpion pie.

Impossible to name all the books that came to me, that came for me. It felt just like that—they came to take me somewhere I needed to go. I know exactly what author and book inspired each of my own novels. The texture of those works, the self-possession of those authors, led me into uncharted places that invited exploration. Books as ice-breaking vessels.

For many years I knew Louise Erdrich’s work only because on the shelf in the bookstore her novels sat just to the left of mine. Her many fine novels. If someone asked me where to find my work I’d tell them, “To the right of Louise.” I began to think of myself somewhat impersonally as The One to the Right of Louise. Her novel, The Round House, is a brilliant book which brought me to a recent understanding: The work of monsters is to alert us to our own human fallibility, but in doing so a monster must be fallible too. There must be a chink in the armor that displays the ancient wound. Otherwise, there is no push and pull, no tension at work. Medusa lost her head without even a cry of disbelief. She’s a poor fictional choice because she lacks complication.

Erdrich’s villains are complex, corruptible, fallible and human. Her heroes metaphorically wander in the Labyrinth at the mercy of the Minotaur, a half-man half-bull monster, until they discover the strength in their own hands and pummel the creature to death. But unlike the mythological Theseus, they live with the complications murder brings. Mythology is real and unreal, representational and hyperbolic all at once. It demonstrates and is at the same time short on practical advice. Unlike fiction which sets down a moral thread, mythology shies away from morality and especially moral endings. It’s rife with pettiness and emotional outbursts that often lead to violence. It only inconsistently extends redemption. Nonetheless, at the time of some of the deepest uncertainty I have known, along came gods, mortals and monsters to offer me a pair of winged sandals and a way out. That was me on the cover of Edith Hamilton’s Mythology. No, not the severed head. I am the one with the sword.