This week’s Letter from Home is brought to you by the color yellow: egg yolks from free-range chickens, aspen leaves in the fall, and sunflowers that bloom along roadsides in August in northern Arizona, in fields and yards all over town, playing against the clear blue sky and swaying when the wind comes up. And tiny goldfinches and pine siskins perching on those tall stalks, hanging upside down and helping themselves to the seeds.

This week’s Letter from Home is brought to you by the color yellow: egg yolks from free-range chickens, aspen leaves in the fall, and sunflowers that bloom along roadsides in August in northern Arizona, in fields and yards all over town, playing against the clear blue sky and swaying when the wind comes up. And tiny goldfinches and pine siskins perching on those tall stalks, hanging upside down and helping themselves to the seeds.

All this yellow makes my heart sing. And also sink, knowing that those sunflower blossoms signal the beginning of the end of summer, a precursor to the brilliant transformation of aspen leaves. Around here, people used to predict the date of the first frost when the native sunflowers began to bloom: six weeks until fall, we’d say.

When I was in my 20s I wanted bright yellow kitchen countertops. I saw them once in the 1970s, in a house my parents were looking to buy and thought they were the most cheerful and lovely things I’d ever seen. I relished the idea being greeted every morning by a sunny kitchen, even on the gloomiest winter days. Back then laminate countertops were de rigueur, having supplanted porcelain, metal and hardwood, and long before granite became king.

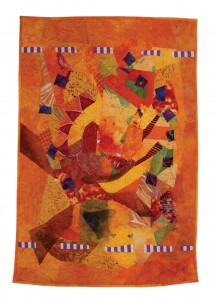

For several years in a row, every December I made a piece that was predominantly yellow, craving those particular wavelengths around the winter solstice. In the ’80s and ’90s it was tough to find much of a selection of yellow fabrics, until I discovered the satisfaction of dyeing my own range of yellow cottons and silks.

For several years in a row, every December I made a piece that was predominantly yellow, craving those particular wavelengths around the winter solstice. In the ’80s and ’90s it was tough to find much of a selection of yellow fabrics, until I discovered the satisfaction of dyeing my own range of yellow cottons and silks.

The earliest oil painters used ochre minerals to make yellow paints, and then lead- and arsenic-based pigments came along. Indian yellow was derived from the urine of undernourished cows (fed only mango leaves and water) in India until 1883, when the process was banned as inhumane. Synthetic yellow pigments weren’t developed until the early 19th century.

During the Renaissance, the robes of Judas Iscariot were almost always portrayed as yellow to symbolize betrayal, envy and duplicity.

In 1888, around the same time he painted Sunflowers, Vincent Van Gogh waxed eloquent about yellow in a letter to his sister: “The sun, a light that for lack of a better word I can only call yellow, bright sulfur yellow, pale lemon gold. How beautiful yellow is!”

My great grandmother’s sewing book advised “blonds should never choose harsh strong colors, and they should shun yellow and orange.” My Aunt Nina thought it fitting to give me that book last summer after she discovered that my great-grandmother had used the volume the way other families use the family bible. She kept notes in the front detailing the dates of her marriages and children’s birthdates:

Married to John M. Kapp on March 25, 1905

First borned Teresa C. Kapp Jan. 4, 1906

2 borned Charles E. Kapp, Sept. 18, 1909

John M. died April 14, 1912

I was a widow 9 years

married Walter Cunningham in 1921, June 18

Married 4 years when Jack was borned in Sept 7, 1926

None of her children had yellow hair. Great-grandmother also wrote in the back of the book: “Went to the 5 and 10 cent store. Be back in a while. Mom.” The note reads like a belated telegram from 1945 from a woman I never met. I imagine her walking to the dime store for thread or buttons wearing her sensible shoes and a yellow dress printed with tiny flowers.

Printers developed four-color process printing in the late 1800s, allowing newspapers to more easily add color images to their publications. According to Wikipedia, “The Yellow Kid (1895) was one of the first comic strip characters. He gave his name to a type of sensational reporting called Yellow Journalism.”

Historian and journalist Frank Luther Mott defined yellow journalism as using:

- Scare headlines in huge print, often of minor news

- Lavish use of pictures, or imaginary drawings

- Faked interviews, misleading headlines, pseudoscience, and a parade of false learning from so-called experts

- Emphasis on full-color Sunday supplements, usually with comic strips

- Dramatic sympathy with the “underdog” against the system.

Parts of that list could be applied to some so-called news channels these days.

There’s the dark side of yellow, too. Yellow can be toxic like yellowcake uranium, or the mustard yellow mine waste (containing cadmium, lead, zinc and arsenic) now flowing down the Animas River, then towards the San Juan River, Lake Powell and the Colorado River. Yellow six-pointed stars of David were sewn to the clothing of Jews in Nazi Germany to designate their marked status.

Yellow may not be everyone’s favorite color, but it’s useful to attract attention: a yellow caution light, a yellow school bus, a yield sign, a yellow cab, the saffron- or turmeric-dyed yellow of a monk’s robe.

More flowers are yellow than any other color, the better to attract pollinators. The yarrow in my yard is a paler, cooler yellow than the sunflowers. The coneflowers are more saturated and warmer—almost orange—like the sun on a day when smoke filters the sky. Columbine flowers look benign enough, the palest yellow of their spurred petals gradating to buttery yellow at their centers, but the seeds and roots contain cardiogenic toxins that can cause deadly heart palpitations and gastroenteritis. In the spring, the yellow-green dusting of ponderosa pine pollen can set off our allergies.

Yellow is also the color assigned to the chakra at our physical center—the solar plexus—from which a complex network of nerves radiate. Love yellow or hate it, I say trust your gut.